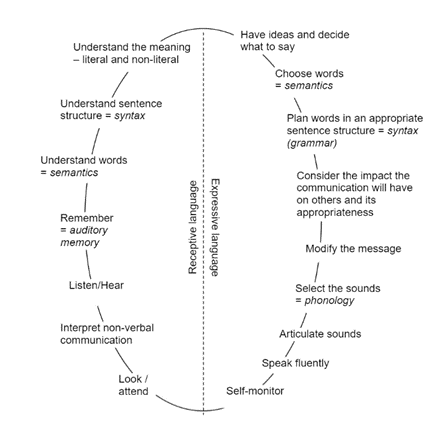

Understanding language is the ability to make sense of both spoken and written information. It requires several skills. The Elklan ‘Communication Chain’ (below) shows the sequential skills involved – in particular, the ‘receptive’ language (left-hand) side of the chain.

The initial skill shown is ‘Look/attend’, progressing clockwise around the chain.

Communication chain shared with permission from Elklan.

Students who struggle to understand language may also demonstrate difficulties with their attention and listening skills, as well as having a limited vocabulary. In addition, their difficulties in this area may well impact on their behaviours. It is not unusual for these students to display a higher level of understanding (receptive language) than in their level of spoken language (expressive language).

A student with Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN) may:

- find group/whole class work tricky, e.g. following instructions, maintaining concentration for lengthy tasks, rely on their observation of peers to complete activities.

- create/seek distractions, e.g., make poor behaviour choices, change the topic of discussion.

- Read fluently, often from quite complex texts, without any understanding of what they have just read.

Adults can support SLCN students by:

- Gaining the student’s attention before talking, e.g., say their name before issuing an instruction or asking a question. Face them so they can see your facial expression and your lip movements

- Keeping language simple and direct, e.g., giving short instructions; splitting longer ones up into smaller chunks.

- Giving the student time to think & then respond to you. This is their processing time, and they will need longer than their peers to do it proficiently.

- Pre-teaching and highlighting key vocabulary (see section on vocabulary).

- Providing visual representations of what you want them to learn. E.g., vary your delivery by mixing speech with video clips; provide visual word lists; use gesture to help their understanding. Be aware of your tone of voice and other non-verbal communication.

Specific areas of difficulty:

Verbal reasoning

Verbal reasoning is the ability to understand, and reason (work through), concepts or problems expressed in words. Verbal reasoning tests can demonstrate how well a student can lift meaning, information and/or implications from a text.

Students who need to develop their verbal reasoning skills benefit from a structured approach to language being used by adults across the curriculum. The Blank Language Scheme is one example of such an approach. This language scheme is based upon the work of Blank, Rose and Berlin (1978), and it supports the development of verbal reasoning and abstract language. Their model splits these areas of language into four steps, or levels:

- Level One (lowest level) – Naming – e.g.

- Looking for a matching object: “Find one like this”

- Finding an object by sound: “Show me what you heard”

- Level Two – Describing – e.g.

- Finishing a sentence (sentence completion): “You cut with a… “

- Concepts: Naming parts of an object or what it does (e.g. pen lid): “This is the... “

- Level Three – Retelling – e.g.

- Concepts: Defining a word: “What is a…?”

- Giving a set of directions: “Tell me how to…”

- Level Four (highest level) - Justifying – e.g.

- Justifying and explaining a prediction: “Why will…?”

- Explaining the logic of compound words: (e.g. handbag, football) Why is this called…?

For more information on developing each level, view this leaflet.

Use of this model can support:

-

Students to understand increasingly complex levels of questioning

-

Students to understand abstract language

-

Students to develop their abilities to make inferences

-

Classroom practitioners to differentiate their questions for different levels of learning and in different contexts. E.g., lower levels of questioning may be required when asking a student about behaviour-linked incidents from breaktimes, than when questioning the same student in a calm classroom.

The format of the questions and levels remains the same whatever the age/ability of a student. It is the vocabulary, resources and texts which are altered according to the student's needs.

Sarcasm, idioms, and jokes (non-literal, ambiguous language)

Students who have difficulties with understanding language may also demonstrate an inability to understand sarcasm, idioms, and jokes. Also, the language used in these expressions is usually dependent on the context in which they are used. Other areas contributing to confusion may be:

- The use of nonverbal communication by the speaker, e.g., the tone of their voice

- The social sophistication of the speaker – they may actively seek to control the confused listener through their personal knowledge of non-literal language.

Non-literal language is used quite frequently and unless a student gains familiarity with alternative uses of language/words they may struggle and 'switch off' from attempting to join in groups or form friendships. Later, in adult life, these difficulties can impact on the success of SLCN students entering the world of work.

To understand and use non-literal language, students need explicit support to:

- Spot the use of non-literal language in their everyday situations

- Learn the most used idioms/sayings used in their everyday lives by peers, supporting staff and family; be taught what these idioms/sayings really mean. This can be reinforced using carefully selected clips from TV programmes and films.

- Could observe others telling/receiving jokes or sarcasm. This helps with their understanding in context, along with the range of possible reactions. For example, reacting to a joke told by a classmate would be different to the reaction to one told by a Principal/Head Teacher.

- Have frequent exposure to the use of the above examples of non-literal language, along with the opportunity to discuss it with a supporting adult

- Form a library of idioms/sayings for reference in the absence of usual supporting adults. This can then be reviewed as the student moves into different age groups and settings

Links to literacy:

Grammar and punctuation

Students who find the processing of information and comprehension a challenge may also have difficulties with grammar and punctuation. Some of these students may have a social use of talk which is at a higher level than their actual processing capacity (i.e., higher than their level of understanding).

For students to understand grammar effectively they will need explicit teaching, know which strategies help them be independent.

Their use of grammar may be immature, including their use of:

- Past irregular verbs

- Passive tense

- Irregular plurals

- Pronouns

- Conjunctions

- Punctuation marks

General support strategies:

- Teach students to reflect on their own use of grammar.

- Set SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, and Timely) to guide the student towards areas of focus.

- Consider the use of colour-coding or highlighting, 'cloze' procedure, and similar activities to draw their attention to correct usage of grammatical structures.

- Past irregular verbs – help the student to look for patterns, e.g., feel>felt; sleep>slept; keep>kept. Some verbs which are commonly used and do not have patterns, e.g., is>was go>went; will need to be learnt through precise teaching and modelling.

- Model saying & reading basic sentence using different voice tones and emphasis.

- Model the ‘reading’ of punctuation. For example, what do you do when reading a full-stop, comma or question mark? Stress voice changes, taking a breath.

- Prepare passages to be read aloud prior to the lesson. Rehearse reading a passage to give the student time to organise their approach.

Activities:

- Comic Strip Conversations (Gray, 1994). These can be effectively used to analyse the social use of non-literal language in real-life situations by recording in drawings, who was involved and what was said. Drawing a response ('resolution') to when this happens again.

- Encouraging students to think what a saying means if we take it literally, makes sense.

- Incorporate commonly used sayings into everyday life experiences. E.g., "We're a bit pushed for time to complete this job now. Let's finish it tomorrow" used by a supporting adult at the end of a practical lesson such as DT. When the student attempts to use the same saying, praise them and explain/model correct form if needed.

- Language for Behaviour and Emotions, by Anna Branagan, Melanie Cross and Stephen Parsons, contains sections on solving people problems and understanding crazy phrases (idioms), and includes non-standardised assessments.

- Language for Behaviour and Emotions, by Anna Branagan, Melanie Cross and Stephen Parsons, contains scenarios to discuss with young people. Each scenario has an accompanying short story and ideas for questions arising from the story. These resources can be re-produced for whole class, group or 1:1 work. The stories lend themselves to the reading of punctuation (see above).

- Language for Thinking, by Anna Branagan and Stephen Parsons, follows a similar approach to the Language for Behaviour and Emotions, but is aimed at younger students who find reading tricky.

It may take lots of repetition of one saying over a long period of time for the student to understand and then use it.

Training

- Elklan Training (‘Speech and Language Training for 11-16s’; ‘Speech and Language Training for Vulnerable Young People’) includes a module on the Blanks model. This training is available for practitioners and parents/carers of children from Early Years to Adulthood (with a variety of SEN).

-

Contact the ECLIPS Team for the local training offer on: ECLIPS@lincolnshire.gov.uk, or view information on the Lincolnshire County Council website. You can also contact Elklan via their website.

-

Resources

- The ‘Test of Abstract Language Comprehension’ (TALC) assesses the Blank level of a student. There are two versions available: one for Primary and the other for Secondary use.

- Resources which contain links to the Blanks levels include:

- Language for Thinking, by Anna Branagan and Stephen Parsons, Routledge, 2013. A resource aimed at the primary age range but may be useful as a guide for KS3 pupils with SLCN. It promotes children's development of inference, verbal reasoning and thinking skills.

- Language for Behaviour and Emotions, by Anna Branagan, Melanie Cross and Stephen Parsons, Routledge, 2021 - A resource for secondary pupils with speech, language & communication difficulties, social, emotional, and mental health needs. It a programme which supports gaps in language, vocabulary, and emotional skills.

- Secondary Language Builders: Advice and activities to encourage the communication skills of 11–16-year-olds, Elklan Publishing, 2021.

- Language Builders for Vulnerable Young People, Elklan Publishing 2018.

Websites

- The Communication Trust and Consortium/I Can: Supporting those that work with children and young people with their speech, language, and communication.

- Popplet: create mind maps online, also available as an app.

The term vocabulary encompasses the words we use and their meanings and associations; this includes stated definitions and all the general links and understanding of a word created by personal life experiences and contexts. To be able to learn and use new vocabulary successfully, words need to be stored in the long-term memory and retrieved when needed.

Learning vocabulary is lifelong. In school young people are exposed to new words every day that represent the concepts that they are being taught, this can be directly (where students are taught individual words using word learning strategies) or indirectly (through reading or being read to, writing, listening, and engaging in spoken language with adults and peers). Through whatever means a student is exposed to new words, they are expected to learn and remember them; and as they progress through education, academic vocabulary becomes more complex, technical and abstract.

The link between vocabulary knowledge and academic progress is strong. There is a huge amount of research that shows that it is one of the most significant factors in relation to students achieving higher grades in English Language, English Literature and Mathematics. However, there is also much evidence that proves that there is a vocabulary gap, and it starts early, before children have even started school. The gap can increase throughout the school years and children with reduced vocabulary can have difficulty achieving their potential, including during exams and can reduce their future life chances. If we can close vocabulary gaps in the classroom between these students and their peers, we are setting them up with the tools needed for academic success and the vital skills needed to be able to communicate confidently in society and life after school.

Identifying difficulties with vocabulary and concepts

Young people may be experiencing difficulties with vocabulary and concepts if they:

- use non-specific language (e.g., stuff, thingy)

- sound immature for their age with the language they use

- struggle to understand what is asked of them

- hesitate in giving a response or respond too quickly with an incorrect response

- omit words

- use inconsistent word endings

- substitute words of similar sound or meaning i.e. ‘light ball’ for lightbulb or

- use gesture and/or appear to be searching for words

- often forget new vocabulary/need more time to remember it

There may be different reasons why young people have poor vocabulary. It could be caused by general learning difficulties or specific difficulties associated with learning and remembering new words; limited world knowledge; or difficulties with word finding and retrieving words stored in long term memory.

Remember: Vocabulary difficulties can also underlie behavioural issues such as anxiety or misbehaving in class.

The three tiers of vocabulary

Words can be grouped into three tiers

Many secondary aged students still need focused support of Tier 2 vocabulary, and explicit teaching is essential. Teaching staff need to be aware when Tier 2 words are used in the classroom, especially if they are being used to teach Tier 3 words and to check understanding with students. Any difficulties understanding Tier 2 vocabulary can significantly affect a student’s ability to learn new information and therefore successfully access the curriculum.

Up to 10 Tier 2 words could be targeted at a time using the vocabulary strategies discussed in this chapter. If students are encouraged to use the targeted words across curriculum areas it will support learning, understanding and transfer into long term memory.

Tier 2 words are particularly important in understanding examination questions which use words such as ‘examine’, ‘compare’, ‘evaluate’ and ‘discuss’. The understanding of these tier 2 words can have a profound impact on the student’s ability to answer the question accurately.

General classroom strategies to develop the vocabulary of all students

- Differentiated vocabulary lists for each student depending on individual need

- Group vocabulary into 3 areas: Essential (core); Desirable (useful words); Might be nice (peripheral, abstract) e.g. When working on photosynthesis the words: energy, oxygen, carbon dioxide and chlorophyll might form part of the essential words a student needs to learn; while it might be desirable for a student to learn the words chloroplast, diffusion and glucose; the ‘might be nice’ words may consist of vocabulary like palisade cell, stomata and autotroph

- Use language all students can understand to explain new words

- Ask students to recap and provide their own explanations for word meanings

- Provide frequent opportunities for repetition and reinforcement and revisit new words regularly

- Important for students to say the word as well as listening to it and discussing meaning

- Use multisensory (kinaesthetic) learning: see it – visuals; hear it; say it – individual words and create sentences; read it; write it - individual words and create sentences

- Encourage students to highlight or underline any tricky words that they do not know, or understand

- Encourage students to keep a vocabulary journal of words that they have identified as tricky, with explanations, definitions and visuals

- Promote independent use of dictionaries and thesaurus, to support vocabulary journal

A ‘Do I Know This Word?’ card (developed by Communication Trust) can be used to identify a student’s knowledge for a range of words. Any that need additional support are then identified.

Word learning and word finding strategies

- Essential, Desirable, Might be Nice - Decide on a realistic number of words the student needs to learn, pre-teach them, revisit them often.

- Vocabulary notebook/journal - Any tricky words the student has identified are written into their journal, with ideas about word meaning, descriptions and sketches. TA support to write the word in syllables to aid pronunciation and correct word storage.

- Mindmaps - A network of words and/or images based around a specific topic; these can be paper based or use an online app such as ‘Popplet’.

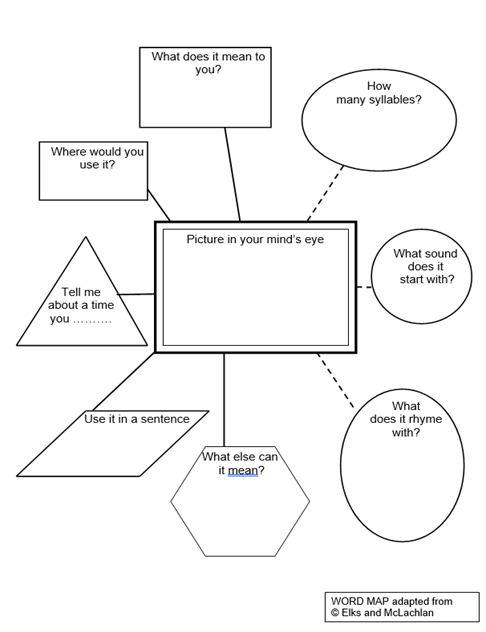

- Word maps - A map of ideas about a word or concept, combining information about what a word sounds like (phonological links) with the word meanings (semantic links). See below.

- Word Wise Whiz support cards - A quick activity that can be used during lessons or at the end of a session to revisit a new word – Think of a meaning (think of two things about what the word means), think of a sound (what sound does it start with, what does it rhyme with), think of a sentence. See below.

- Other word investigations - Including: word storm, word bluff, true or false, word connections, word choice, multiple meaning tree, spidergramme, attribute web

- Word derivatives (word morphology) - Create lists of root words, pre-fixes and suffixes; give to students and see how many real words they can recognise and create. Use these words to start discussions and check understanding, also use in sentences and real contexts to embed learning.

- Say it in syllables - Model long words in separate syllables, get students to listen and then repeat.

- Quick word games - Quizzes, hangman, word searches, bingo, vocabulary lotto

Linking semantic and phonological information

Vocabulary learning is most effective when phonological (sound) and semantic (meaning) information is linked. It is important for students to say the word, break it into syllables, think about other words it rhymes with, and the sound it starts with, as well as listening to it, discussing meaning and using it in a sentence.

Word maps (included with kind permission from Elklan) are extremely effective in supporting the acquisition of new vocabulary and incorporate both semantic (look below at the questions and suggestions linked with a solid line) and phonological information (the questions below linked with a dashed line). They are excellent to use with more technical, abstract words; and are similar to a mind map, but only focus on one word rather than a topic. Encourage students to use them independently and keep them so students can refer back to them.

Word Wise Whiz cards (also included with kind permission from Elklan) are a quicker, more condensed version of a word map that can easily be used in classrooms, during lessons or at the end of a session to revisit a new word.

Links to literacy

Vocabulary is a very important part of reading and writing. As students start to read more challenging and advanced texts they must learn and remember the meanings of any new words that are not a part of their oral vocabulary at the time, otherwise the text can lose much, if not all of its meaning. It is important to remember this and check on understanding even if a student can read a text without difficulty, as problems with vocabulary rather than reading can lead to a lack of understanding and comprehension difficulties.

As they get older, students are expected to learn many new words through reading and writing. However, learning through reading is not easy, especially if a student has speech, language and communication needs. The word has to be decoded; then the student has to recognise that the word is not known. If they have identified this, they then have to then obtain meaning usually by reading around the word and extracting meaning from other words and sentences; they also have to remember the new information.

To do this successfully, students need to be able to concentrate, be self-aware, motivated, and have strong language skills and verbal reasoning skills.

Many students will need some form of extra support and additional strategies.

Resources and references

Training

- Elklan Training (‘Speech and Language Training for 11-16s’; ‘Speech and Language Training for Vulnerable Young People’) includes a module on Vocabulary.

Books

- Secondary Language Builders: Advice and activities to encourage the communication skills of 11-16 year olds, Elklan Publishing, 2021, included in the training, or extra copies can be purchased on the Elklan website.

- Vocabulary Enrichment Programme: Enhancing the learning of vocabulary in children, by Victoria Joffe, Routledge, 2011

- Closing the Vocabulary Gap, by Alex Quigley, Routledge, 2018

- Language for Behaviour and Emotions, by Anna Branagan, Melanie Cross and Stephen Parsons, Routledge, 2021 (A new resource for secondary pupils with speech, language & communication difficulties, social, emotional and mental health needs. It is to support gaps in language, vocabulary and emotional skills).

- Bringing Words to Life: Robust vocabulary instruction, by Isabel L. Beck, Margaret McKeown and Linda Kucan, Guilford Press, 2nd Edition, 2013 (Provides a framework and practical strategies for vocabulary development).

- Language for Learning in the Secondary School: A practical guide for supporting students with Speech, Language and Communication Needs, by Emma Jordan and Sue Hayden, Routledge, 2011

Websites

- The Communication Trust and Consortium: Supporting those that work with children and young people with their speech, language and communication.

- Thinking Talking: Free vocabulary resources for schools (many different games uitable for primary or secondary).

- Afasic: Produces a range of information and training materials for professionals who are working with children and young people with speech, language and communication needs.

- Popplet: create mindmaps online, also available as an app.

- Wordwall: Make your own engaging, interactive activities, including word games.

- EduCandy: Create interactive online games that you can share with your students.

- Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English: To create student-friendly word definitions.

- The Visual Thesaurus: Is an interactive dictionary and thesaurus which creates word maps that blossom with meanings and branch to related words.

Expressive (or spoken) language is the term used for when we put our thoughts and ideas into words and sentences. There are different elements to expressive language, including words (vocabulary), grammar and pragmatics (using language appropriately).

This section aims to provide you with an outline of what to expect from students at secondary age along with some ideas on how to encourage expressive language development.

There are strong links between language and literacy as you will see throughout this resource. Young people who experience difficulties with language often have associated literacy difficulties (1). There is evidence that opportunities for students with SLCN are increasing, however, their peers continue to outperform them, gaining twice as many qualifications at the end of compulsory education (2).

A note on students who are acquiring English as an additional language (EAL):

The time students spend with their peers is the best language learning opportunity as it

is easier for the student to learn from their peers. Peers act as natural role models. Students who acquire a new language often develop language to enable them to chat and make friends initially (within approximately two years of acquiring a new language).

The language used within the school environment can take longer for a student to acquire. It may take up to five years to develop proficiency in ‘academic language’ (Cummins 2000).

Top tips to support students acquiring English as an additional language include:

- Encourage the development of a student’s home language as this will enhance the learning of English. Therefore:

- It is okay for students to speak in their home language when they are at school

- It is okay for children to mix English and their home language in one sentence

- Parents should be advised to speak the language/s they feel most comfortable in. It is the quality of parent – child communication that is important

- Familiarize yourself with the languages and cultures of the children in your class - e.g. learn some common words/vocabulary in the other language.

- Children learning an additional language commonly go through a silent period, where they may say nothing for several months in the new environment. This is a natural process. This should not be confused with a selectively mute child.

- Give the child time to:

- listen and respond

- become familiar with the language

- adapt to school routine

- It is important to value the child’s home language and culture by using culturally appropriate resources within the school setting. Bilingualism can be a positive force in children’s development, so it is important for their home language to be promoted by the school.

- Immerse the child in a language rich environment from the start – minimise time out in special EAL classes.

- Activities that are good for EAL students will benefit all students

There is considerable evidence that learning to speak and use more than one language can benefit children’s overall academic and intellectual progress.

(Top tips shared from Shah and Mathur: London SIG Bilingualism 2009)

The Ethnic Minority and Traveller Education Team (EMTET) supports children from minority backgrounds. Further information on the support EMTET offers and how to contact the service can be found on Lincolnshire County Council's website.

What to expect from students:

By age 11Students should be able to: |

By age 13/14Students should be able to: |

By age 18Students should be able to: |

|

|

• Use a range of joining words in speech and writing: provided that, moreover • Tell Interesting and entertaining stories that have lots of detail. The thread of the stories are typically maintained • Explain the rules of a game, or provide directions/instruction a in a simple but accurate way

|

(Speech and Language UK)

Additional information can be found within ‘What’s Typical Talk at Secondary’. The poster and further resources can be found on Talking Point's website.

It is not uncommon for secondary aged students to present with residual difficulties at stages 3 and 4 of the table below.

|

|

Stage 1 |

Stage 2 |

Stage 3 |

Stage 4 |

|

Plurals |

’s’ ending |

‘es’ ending |

‘ves’ ending |

Irregular |

|

Negative |

no |

not |

can’t don’t won’t |

didn’t wouldn’t |

|

Possessive |

’s |

|

|

|

|

Pronouns |

I, me, you, it |

he, she, him he |

we they us them |

yourself, itself etc |

|

Prepositions |

in, on |

under, behind |

in front, next to, |

between, through |

|

Question words |

what |

who, where |

when, how |

why |

|

Basic time concepts |

again, now |

today, after |

yesterday, always, before |

tomorrow, sometimes, never |

|

Tenses |

sit go run |

ed endings |

irregular ‘past’ |

future tense |

|

Joining words |

‘and’ with nouns |

‘and’ in phrases |

because, but |

so, or, until, while, since, therefore, although |

N.B. Be aware that the above stages are developmental. This means that the pupil will need to understand consistently at, for example, Stage 3 before working on their expressive communication using the structure. Only then can they move onto Stage 4 concepts etc.

Recognising expressive language difficulties

Pupils who are experiencing difficulties expressing themselves may:

- use short utterances

- have limited vocabulary

- have difficulty in finding the right word

- use immature or unusual grammatical structures (see table above)

- confuse the order of words

- have difficulty in sequencing ideas

- have a literal use of language

- lack flexibility and have difficulty generalising learning

- be extremely passive

- show frustration through their behaviour

- Begin to explain and then give up

Supporting expressive language skills:

Recast - Everyday language models

Recasting is a way of offering students clear, simple language models that reflect their own language attempts. This ensures that models are provided just at the right level. You do not need to ask them to repeat or repair their production. Just listening is helpful.

Recasting is useful as it is a technique that does not obstruct the natural flow of communication. A recast occurs when the adult modifies a student’s sentence by adding new or different grammar or word meaning information. The adult is simply repeating the ‘right’ way of saying the sentence.

Extend vocabulary

Wherever possible try to extend vocabulary through normal conversation by repeating the student’s sentence back to them and adding one word or piece of information.

Student – “the man’s going there” Adult – “the man’s climbing up the ladder”

Student - “the work is tricky” Adult - “yes this experiment is complex”

Model improved sentence structure and grammar

When a student uses a short or out of sequence phrase or sentence, repeat back what they have said but modify the language to make it more adult.

Student – “I broked my glasses yesterday Miss” Adult – “Oh no! You broke your glasses yesterday.”

Student - “He leave him alone all by him on him alone” Adult - “He left him all by himself.”

Student - “She felled down the stairs and broken his glasses” Adult- “yes, she fell down the stairs and broke her glasses”

Student - “Me can do that!” Adult - “I can do that too!”

‘Recast’ in normal conversation

Encourage all adults to take opportunities through the day to recast in this way as a natural part of conversation.

Set aside time to talk - share and discuss pictures

Try to set aside a specific one to one or small group talking time. It is very helpful to have a visual basis such as a picture book or sequencing cards to discuss. Use this time to recast. During structured sessions like this encourage students to try repairing their production, following the model you offered them.

Additional strategies to support expressive language:

- Praise students’ non-verbal communication

- Listen to students’ ideas, feelings and experiences

- Encourage students to support each other to elaborate or add detail to what each other say – give opportunities for group discussions and provide guidance on how to work together. As students become older, they are expected to become more independent with their learning. Unfortunately, the opportunities for them to rehearse language verbally reduces

- Manage turns to talk in the classroom by shared routines rather than ‘bidding’, this will support students to get involved in whole class talk

- Ensure that those who are not speaking are actively participating

- Respond to mistakes as though they are an opportunity for learning – model and recast (add link to previous section)

- Children are given time to think; 10 second rule is in operation

- Provide everyone with the opportunity to talk

- Ensure there is always plenty to talk about/opportunities to talk within lessons

- Use lesson conclusions as opportunities for students to talk and reflect on what has been learned - summaries

- Attempt to provide have opportunities for students to engage in structured conversations with peers and teachers

Additional resources:

The resources below have been included in this website with the kind permission of Elklan®. Please see the Elklan website (4) for further information on training and available resources.

Students with difficulties expressing themselves will find it hard to write essays/stories for many reasons including: lack of imagination, sequencing difficulties, difficulties formulating sentences. Use narrative frameworks or writing frames to support spoken and written language. Incorporate elements such as: Who? What? When? Where? What happened?

Listening to students:

It is hugely important to listen to students’ views and for students to tell us what is important to them. Time should be spent encouraging students to understand their needs and for them to express the area/areas they feel they require support with.

This process encourages students to become more engaged in their learning as well as provide them with ownership of their achievements. This is often known as a strategy-focused approach. Research has found strategies such as listening to parents as models, practising words and asking for help have been identified as useful by young people (5) In one study, teaching strategies such as the use of visual organisers, ‘pause time’ for planning, and ways of recognising feedback to support self monitoring resulted in positive outcomes in both written and spoken language (6).

References:

- Snow, CE, Porche, MV, Tabors, PO and Ross Harris, S (2007) Is Literacy Enough? Pathways to Academic Success for Adolescents. Paul Brookes Publishing

- Conti-Ramsden, G, Durkin, K, Simkin, Z and Knox, E (2009) Specific language impairment and school outcomes: Identifying and explaining variability at the end of compulsory education International: Journal of Language and Communication Disorders Vol 44 (1)

- Speech and Language UK: Changing yound lives

- Elklan Training Ltd

- Spencer, S, Clegg, J and Stackhouse, J (2010) ‘I don’t come out with big words like other people’: interviewing adolescents as part of communication profiling Child Language Teaching and Therapy Vol 26 (2)

-

Singer, BD and Bashir, AS (1999) What are executive functions and self regulation and what do they have to do with language learning disorders? Language, Speech & Hearing Services in Schools Vol 30 (3)

Speech sound development -ages and stages

The table below outlines the ages at which we would expect different sounds to be present in a student’s speech. Sometimes a student may be able to produce the sound at the start or end of a word but is not yet using this in other words or positions; this usually means that this sound is developing on its own. However, if you have concerns that the student is not making progress with these sounds, you can refer to our service at any time for an assessment.

You can refer a child to our service by completing our form on our webiste here.

|

Sounds |

Age acquired by: |

|

|

|

in 50% of children: |

in 90% of children: |

|

Vowels |

1 ½ to 2 years

|

3 years |

|

p b m n t d w

|

1 ½ to 2 years |

3 years |

|

k g f h y

|

2 ½ to 3 years |

4 years |

|

ng s

|

2 ½ to 3 years |

5 years |

|

l

|

3 to 3 ½ years |

6 years |

|

sh ch j z v

|

3 ½ to 4 ½ years |

6 years |

|

r

|

4 ½ to 5 years |

7 years |

|

th

|

4 ½ to 5 years |

7 years |

|

zh (as in treasure)

|

4 ½ to 5 years |

7 years |

Residual errors

Some of the young people you work with may have some residual speech and/or language errors.

Speech errors

Some typical residual speech errors may be difficulty with /ch/, /th/, /j/ or /r/ as well as blends such as /pr/, /st/, /sq/ etc.

Supporting residual speech errors –

- adults can repeat what the young person says but using a correct speech model, they don’t need to repeat this back to you, simply model the correct use of the sounds they are finding tricky (e.g. young person: ‘I’ve got a teese sandwich’, adult: ‘oh a cheese sandwich sounds good!)

- It can also be helpful to support residual speech errors by repeating the young person’s sentences back to them to show you have understood them, as well as to correct errors. Don’t ever pretend to understand the student, admit that you cannot understand them and reassure and support them to make themselves understood.

Language errors

Residual language errors might present as using the wrong tense (e.g. running instead of ran) or the incorrect form of the tense (e.g. felled instead of fell). You may also see some small words missing from sentences (e.g. ‘the man running’ instead of ‘the man is running’).

Supporting residual language errors –

- repeat what the student says but using the correct language model, they don’t need to repeat this back to you, simply model the correct use of the language they are struggling with (e.g. young person: ‘he felled down the stairs’, adult: ‘oh gosh, he fell down the stairs, I hope he’s okay’).

If further advice is needed, please don’t hesitate to refer to our service, click here to view our contact us page.

Multi-syllabic words

Young people with residual phonological awareness difficulties may have some on-going difficulties with production of multi-syllabic words. These difficulties can also result in the merging of words within a sentence which can make the young person difficult to understand.

Young people who have weaker phonological awareness are less sensitive to the structure of words. Weaker phonological awareness skills also increase the risk of reading and spelling difficulties.

Phonological awareness requires an understanding of rhyme, syllables and sounds. Phonological awareness activities can be used as a warm-up when starting some intervention with the young person. Visual supports can also be helpful for young people who have difficulty with phonological awareness.

-

Activities to support rhyme production:

Board game – choose a game and have a pack of pictures to use alongside this with a dice. The player picks a card and gives a word that rhymes with the picture/word on the card, if they get it right, they can then take their turn in the game.

Odd one out – draw 3 pictures, two of the words should rhyme and one doesn’t. Take it in turns to choose the two that rhyme.

-

Activities to support syllable segmentation:

Categories – agree a category and then take it in turns to suggest a word within that category. Say the word and then beat/clap out the number of syllables in the word.

Syllable bingo – make some bingo boards with numbers 1-4 written in the squares (each board should be different). You’ll also need some cards with words varying in syllable length on them. The caller picks a card and names it, the players should then put a counter on the number on their board that corresponds to the number of syllables in the word. The winner is whoever is first to get a line.

-

Activities to support alliteration:

I went to the market – one person starts the game by saying “I went to the market and bought a banana”, the next person has to repeat this and add another item beginning with the same sound e.g. “I went to the market and bought a banana and a boat”.

Links with oracy and literacy

Speech and literacy skills use the same underlying processes incorporating speech processing and phonological awareness. Young people who have difficulty reading or who have Dyslexia can have difficulties with speech processing and phonological awareness. Young people who have these difficulties are also vulnerable to difficulties with verbal short-term memory, working memory and understanding spoken language.

Difficulties with understanding spoken language can result in challenges with skills such as inferencing (reading between the lines) and working memory, which can often result in poor self-monitoring skills – these young people may find it more difficult to remain focused and keep on task.

Resources:

Social interaction is a two-way process of communication between two or more people. It involves a range of aspects including talking, nonverbal communication, expression, tone of voice and the ability to interpret and understand what is meant through the use of these skills. This section of the resource will look at how speech, language, and communication difficulties impact on secondary age pupils in relation to emotions, behaviours and vulnerabilities that they face.

Children with SLCN may find some of these areas of communication challenging:

- Listening skills

- Turn taking

- Starting and maintaining a conversation.

- Selecting and expressing ideas and thoughts

- Understanding, reading and using non-verbal communication.

- Understanding the speaker’s intended meaning.

- Asking for clarification or being aware when the other participants require clarification to the points made.

- Being able to modify language/vocabulary to support their understanding further.

- An awareness of the impact of the interaction on other participants.

- An awareness of other participant’s feelings.

- Closing a conversation.

Communication friendly environments

A communication friendly environment is an environment where communication is promoted. It is a space where all students are encouraged to understand, listen, speak and communicate. A communication friendly environment will support the development of all children’s communication skills and usually includes features which will also be particularly beneficial for children and young people with Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN). Developing a communication friendly environment can also be seen as removing barriers to communication.

A communication friendly environment will consider:

- The use of visual supports such as signs, symbols, images, photographs and sometimes writing. There will be clear labels around the classroom to support students in locating resources independently.

- The use of clear and consistent routines and rules within the environment. This assists students who have communication difficulties to understand the expectations and the events that will happen during the day.

- The layout, light and space within the environment. The provision of safe, comfortable and cosy places to have conversations and to talk.

- The level of distractions. Noisy environments are not supportive of listening and communication skills. It is not possible to always have quiet in a busy working classroom but it is important to consider if there are quieter spaces for students to work when they want to talk or communicate.

- The role of adults in the environment. Adults are key to support communication in the learning environment. They will need strategies and approaches to support students to develop key communication skills within the environment.

- How opportunities are planned and created to support communication throughout the day. A communication friendly environment will consider how opportunities can be incorporated into everyday activities. It is important for students to want to communicate; therefore, it is essential that opportunities are planned which will engage and interest the students too.

- The use of displays to support learning and vocabulary development.

- The use of language within the environment. This may include simplified word choices, shorter and more succinct sentences or short and simple instructions.

- Offering students ways to say ‘I don’t understand’ when they are unsure of what is being asked of them or if they do not understand the content of a lesson.

Vulnerabilities

Students who have speech and language difficulties are often more vulnerable in society. Due to difficulties with understanding language they misunderstand the possible consequences that actions may have. They are also less likely to be able to explain their reasons for being involved in actions which are not acceptable and unlike their peers, may not be able to explain their actions and reasoning effectively.

They may find the following difficult:

- Understanding actions have consequences: both positive and negative

- Understanding different interests and hobbies people have so that they can engage in conversations about these with peers.

- Being aware of other people's feelings and emotions

- Understanding how their actions can make other people feel

- Understanding turn taking and initiating conversation

- Understanding sarcasm, humour and idioms

- Being able to ask for clarification if they do not understand something that people have said to them

- Understanding nonverbal communication

- Understanding appropriate word choices

You can help by:

- Setting clear boundaries and explaining the consequences when these boundaries are crossed.

- Encouraging students to talk about their interests and hobbies to encourage varied conversation and different perspectives.

- Commenting on your own emotions and supporting students to discuss their own.

- Modelling discussion about how actions can make others feel

- Modelling and encouraging turn taking and initiating conversation.

- Explaining clearly when you have used sarcasm or an idiom to create a learning opportunity

- Modelling and encouraging asking for clarification

Links between speech, language and communication needs and young offenders

Unfortunately, but understandably, young offenders typically gain attention for complex behavioural and emotional issues within school. However, the cause is often hidden. In fact, statistics show up to 90% of young offenders have underlying speech, language and communication difficulties which are rarely identified prior to entering the criminal justice system. When investigating these individuals, the following areas have been highlighted as particularly difficult for these young people:

- Listening and following direction

- Understanding age-appropriate vocabulary

- Understanding of spoken and written language

- Writing

- Forming and maintaining relationships

- Resolving conflict

- Negotiating

- Social withdrawal

- Low self-esteem and confidence

- Engagement and motivation

- Frustration with demands

It is important to remember that these behaviours are typically not a choice but are a result of unmet speech, language and communication needs and should be investigated further. Such difficulties can reflect on potential early exposure to trauma and managing this. This can create significant challenges which can lead to difficulties with learning, disengagement and frustration.

Speech difficulties can be more obvious than language difficulties. Therefore, language difficulties are more likely to be missed and interpreted as a behavioural difficulty. Without modifications to curriculum and classroom instruction many young people can be disadvantaged. Some students might experience difficulties in school which can lead to social exclusion or anxiety around coming to school.

Emotional Literacy

In order for students to be able to understand other people’s emotions, it is important that they understand their own emotions too. A lot of students with speech and language needs have difficulties in identifying, understanding, and expressing emotions. This can impact on their social skills and interactions, but it can also impact on their literacy skill development in relation to understanding books and texts as well as their writing skills. Emotional Literacy is the term used to describe the ability to understand and express feelings. Emotional Literacy involves having self-awareness and recognition of your own feelings and knowing how to manage them, such as the ability to stay calm when angered or to reassure oneself when in doubt.

Strategies to develop emotional literacy:

- Assess understanding and use of vocabulary

- State the feeling as it is experienced

- Discuss the feelings of others in context

- Use comic strip conversations (see section on comic strip conversations)

- Evaluate feelings during the day

- Explore emotions of fictional characters

- Use games to reinforce learning.

- Songs and visual literacy

- Song lyrics or music videos on mute are effective ways of discussing emotions.

Websites which may be useful for emotions:

Activities/resources to support emotions:

- Emotion charades: Give the students a photo of an emotion or a word card with an emotion written on. Ask them to act it out to the rest of the group and see if the other students can identify the emotion they are acting out. Challenge the group to see if they can find other ways to act out the emotion too

- Feelings scale document

Behaviours

Students who have speech language and communication difficulties are likely to find it a challenge to express their feelings, needs and ideas. This can lead to a high level of frustration and we may see challenging behaviour or withdrawal from the student.

Reasons behind these behaviours: |

|

Difficulties understanding of the questions being asked |

|

Lack of time to process information |

|

Low self-esteem and confidence |

|

Attempts to convey a message through behaviour which cannot be put into words |

|

Difficulties finding the words/sentences to use |

|

Difficulties with peer relationship; building, maintaining, resolving conflict |

|

Frustration that they don’t feel understood |

|

Difficulties pronouncing the words |

This highlights some of the underlying reasons which may be overtly displayed as challenging behaviours in young people.

The starting point for managing this behaviour is to identify and support the underlying difficulties with their speech, language and communication.

Tips for working with young people displaying challenging behaviours:

- Work with them at the level of their individual understanding.

- Assess their needs.

- Help them to develop strategies to cope when they are in difficult situations. For example, asking for repetition of instructions or clarification. These skills can be taught explicitly or within other work.

- Allow means and opportunities for the child to input.

- Give time to the child to process information.

- Provide a safe environment or member of staff for the child.

- Creating communication guidelines or care plans.

- Seek the support of outside professionals to support their development and learning.

Managing and recording incidents

When an incident happens at school it can be helpful to gain insight into the young person’s view of the event and give them an opportunity to go through what happened. Incident forms can be helpful in doing this. This form is specifically designed to use language which is easy to understand and allows an objective explanation to be given.

When completing these forms, it’s useful to monitor your language. The Blank Language scheme (Blank, Rose and Berlin, 1978) highlights that understanding develops in stages and has been taken into consideration. Where understanding is compromised due to a stressful encounter, this can guide you to using a more accessible level of questioning and avoiding questions such as ‘why?’ which can be difficult to answer.

Emotions can also impact on a student’s ability to recount an incident – this form will help the staff member and student summarise the event using simplistic questioning to help ascertain the facts about what happened.

Click here to download this form.

Additional resources to support behaviour:

References

Anderson, S.A., Hawes, D.J. and Snow, P.C., 2016. Language impairments among youth offenders: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, pp.195-203.

Blank, M., Rose, S.A. and Berlin, L.J., 1978. The language of learning: The preschool years. Grune & Stratton.

Branagan, A., Cross, M. and Parsons, S. 2021. Language for Behaviour and Emotions; A Practical Guide to Working with Children and Young People.

Branagan, A., Cross, M., & Parsons, S. (2021). What’s that feeling called? (naming

emotions). In Language for Behaviour and Emotions. A practical Guide to Working with

Children and Young People (1st ed., pp. 328–347). Routledge.

Bryan, K., Garvani, G., Gregory, J. and Kilner, K., 2015. Language difficulties and criminal justice: the need for earlier identification. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 50(6), pp.763-775.

Coles, H., Gillett, K., Murray, G. and Turner, K. 2017. Justice Evidence Base. The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT).

Cross, M., 2011. Children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties and communication problems: There is always a reason. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Gray, C., 1994. Comic Strip Conversations. Future Horizons.

Horowitz, L., Jansson, L., Ljungberg, T. and Hedenbro, M., 2005. Behavioural patterns of conflict resolution strategies in preschool boys with language impairment in comparison with boys with typical language development. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 40(4), pp.431-454.

Law, J. and Elliott, L., (2009). The relationship between communication and behaviour in children: a case for public mental health?. journal of public mental health, 8(1), p.4.

McLachlan, H. and Elks, L. (2015) Secondary Language Builders: Advice and activities to encourage the communication skills of 11-16 year olds.

McLeod, S. and McKinnon, D.H., 2010. Support required for primary and secondary students with communication disorders and/or other learning needs. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 26(2), pp.123-143.

Rescorla, L., Achenbach, T., Ivanova, M.Y., Dumenci, L., Almqvist, F., Bilenberg, N., Bird, H., Chen, W., Dobrean, A., Döpfner, M. and Erol, N., 2007. Behavioral and emotional problems reported by parents of children ages 6 to 16 in 31 societies. Journal of Emotional and behavioral Disorders, 15(3), pp.130-142.

Sanger, D. D., Creswell, J. W., Dworak, J. and Schultz, L. 2000. Cultural analysis of communication behaviors among juveniles in a correctional facility. Journal of Communication Disorders, 33: 31–57.

Snow, P.C. and Powell, M.B., 2011. Oral language competence in incarcerated young offenders: Links with offending severity. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(6), pp.480-489.

The Communication Trust. 2011. Don’t Get Me Wrong. London: Communication Trust

Stammering is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects around 8% of children. Around 5-7% of children who stammer will stop stammering, leaving a remaining 1-3% that will continue to stammer into adulthood.

Stammering can present as:

- repetitions of whole words e.g. ‘and, and, and then I went to the shop’.

- repetitions of single sounds or syllables e.g. ‘p-p-p-please can I have a pen’ or ‘to-to-tomato please’.

- stretching of sounds e.g. ‘sssssorry I didn’t see you there’.

- Blocking of sounds – where the mouth is in position, but no sound comes out.

You might also see these other parts of stammering:

- Facial tension – this can be in the eyes, nose, lips or neck.

- Other body movements – such as tapping fingers or stamping feet.

- Breathing – the student may take a big breath before speaking or may hold their breath.

Stammering is multifactorial, meaning there are lots of factors that influence the onset, frequency and severity of stammering. These may be factors such as family history of stammering, emotions and temperament, rate of speech and speech and language skills.

How to support a student who stammers:

- React normally – continue to listen and maintain eye contact.

- Allow them time to finish without interrupting or asking them to stop or start again.

- Slow your own speech down.

- Give positive encouragement and praise and offer reassurance where appropriate.

- Ensure students take turns to speak and don’t get rewarded for shouting out – ask that students raise their hands to volunteer an answer as opposed to picking people at random.

- Allow a range of responses for the register.

- Reading in unison is usually easier.

- Ask them what helps! – ‘what do you find helpful/unhelpful when you are stammering?’, ‘would you like people to do anything differently?’ – it’s also important to remember these things can change with time.

If further advice is needed or the young person is worried by their stammer, please don’t hesitate to refer them to our service for further assessment and support.

Resources

- The Palin Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Early Childhood Stammering (2nd Edition) was written by two Speech and Language Therapist’s (Elaine Kelman & Alison Nicholas) who specialise in stammering and work at the Michael Palin Centre. You can access further information about this on the Michael Palin Centre for stammering website.

- You can also visit the Stamma website.

This information was co-produced by Lincolnshire Community Health Services NHS Trust and Lincolnshire County Council.